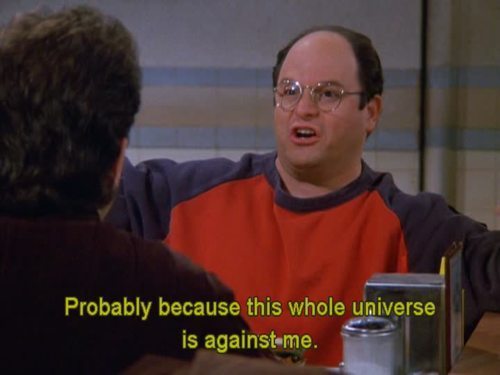

At one point or another, we’ve all engaged in behaviors that hinder our ability to thrive. Aside from the behavior itself, we further limit ourselves by blaming others, temporary insanity, or even a conspiratorial universe. To change behaviors, we must first acknowledge we have more control over our circumstances than we’d like to admit. Willingness to look inward, welcome a change in perspective, then choosing a new behavior is what makes for a successful course of therapy. Simply put, we cannot expect new outcomes if we maintain a rigid denial of personal responsibility. The effort necessary to shift perspective is daunting, but also a necessary prerequisite for change.

We’ve all claimed, “I lost control” or “I went crazy” to explain regrettable behavior, but if we’re being honest, those explanations indicate refusal of responsibility. When clients claim “something came over me” to rationalize behavior, I employ my gift of sarcasm in a clinically relevant way by asking them to describe the demon that has possessed them, or when aliens descended from space and hijacked their ego.

Refusal of accountability extends into the therapeutic relationship when clients expect therapists to heal them with magic wands, or mystical incantations. I’d long hoped for my Good Will Hunting moment to happen, but in reality it never does. Clients’ misconception is that therapists have a miraculous capability to cure when in fact people have an innate ability for self-healing. Humans are the only species who can alter our circumstances through thought and will, but that requires acknowledging our lives as our creation.

This is a sensitive topic for clients battling mental illness; especially those whose symptoms are characterized by repetitive thoughts and behaviors. Once I’ve established trust, I’ve challenged behaviors by focusing on the role of choice. One example is a client who experienced repetitive binge/purge episodes with food. In addition to focusing on all the possible underlying issues, I suggest in the end, choice is involved. At first, I receive blow back such as, “Why would I choose to do this to myself?” or “Do you think I like doing this?” The answer to the second question is an obvious “no”. The answer to the first question is where the therapeutic work lives.

When my client achieved 90 days of abstinence from binging/purging, I further underscored the role of choice by asking who we should credit for such success. Though initially angered when I credited an outside entity with her success, she relented when I noted her selective ownership of choice. To assure her of my own growth process, I shared a moment when I referred to another client’s five years of sobriety as “a miracle”. I was humbled when he reminded me “miracle” minimized his how hard he works at responding differently to his relentless urge to drink.

When clients assume I’m suggesting they want to think or behave in maladaptive ways, I’ve failed to make my message clear. As we all do, clients focus on immediately changing their thoughts when they begin therapy, but I’m not sure they can change without some new experience as a prerequisite. We don’t see our thoughts coming, and our thought patterns are often woven into us through generational processes. Anyone who has ever tried thought blocking knows it to be a tiresome if not impossible feat.

I suggest we focus on changing responses to thoughts, and that behavioral change followed by desirable results rewires our thoughts. This refers back to the role of choice, and my sarcastic ways. When clients respond to my theory with questions such as, “Do you think I choose to hurt myself?” I always answer, “If not you, then who is choosing on your behalf”? We benefit from understanding control over many outcomes is dictated by our will, and we can only change undesirable circumstances through accepting personal responsibility. My belief in this is why I never accept more credit for their growth than should my clients.

Only upon introspection can we identify the ways we avoid responsibility for choice. When we are slaves to external locus of control, personal growth is stunted, maturity is alluded, and anxiety feeds off of belief our lives are controlled by luck, fate, or otherworldly entities. Change begins when we look inward and are willing to accept authorship of our own lives. Owning our choices is often frustrating and scary because it forces us to confront flaws and vulnerabilities, but ultimately we can celebrate how powerful we are while basking in assurance we were never “crazy”, “possessed by demons”, or overtaken by aliens.