Tom slumped in the chair opposite mine. At 62 years old, he was toned, dressed in cycling gear, and appeared at least ten years younger; except for his face. He wore a weathered countenance the most prominent features of which were a frown and red, swollen eyes. Tears are common when I ask clients “what brings us together?”, but it was evident on that day, Tom had cried at home, on his bike, and in my foyer. When he divulged his reason for visiting me, it was even clearer he had been living the same anguished pattern for five months.

He had been by crippled by grief since the Winter death of his wife with whom he spent half his life. Before their life became monopolized by Cancer treatments and poor prognosis, they launched two children, and hoped to embrace their emptied nest with travel and quiet nights on their porch. But his nest was now emptier than he had expected, and instead of reflecting with his wife on lives well lived, Tom sat with a therapist, head in hands, and vomited regrets about twenty year-old fights, withheld apologies, and missed chances. With each repentance, Tom grasped at a missed opportunity, only to have each one elude him.

No longer a husband, and with fatherhood responsibilities decreased, Tom felt undefined. Although he didn’t expect to have fully accepted his loss, Tom was certain his sadness intensified daily. With my help, he hoped to dig up purpose buried under mounds of grief. After I saw Tom out, I trudged back to my office with shoulders slouched, and slumped in my chair.

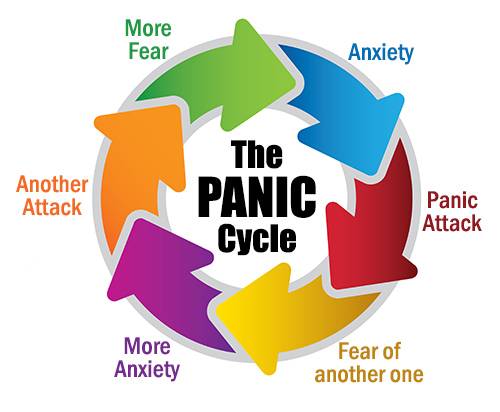

On my drive home, I recounted Tom’s despair, and noted it as unique because unlike clients who sought relief from anxiety and depression, I wasn’t sure if I believed Tom would ever recover from the death of his wife. At that moment I realized I was questioning my own resilience should my wife pass, and I had projected my hopelessness on to Tom.

When I was younger, I dismissed my death as fictitious, and because I doubted I would ever love someone enough to grieve as deeply as Tom, I scoffed at loss. Now as 50 approaches, my death is certain if not imminent. While it is true I am fearful of my own demise, I am far more haunted by the potential death of my wife, and although I know people who have repurposed their lives after a spouse passes, I see myself only as a shattered oyster whose pearl was ripped away.

When those thoughts creep into my mind, I become convinced everything will be behind me, that now is the apex of my life, and that without her, decline is steep. The voice goes on to assure me to care for another is insult and infidelity, and that I will die alone.

It’s all anxiety, of course. My wife is not ill, I have no reason to “kill her off”, as she accuses me of doing when I share these thoughts with her, and I am clueless as to how I will navigate loss.

In subsequent sessions, Tom and I reflected on love as a gift, and how feeling, or fearing loss confirms our acceptance. Weeks later, he weeps a little less, and moves a few steps forward. It is an awesome paradox that we allow someone in so deep, the loss would cause emotional wounds, yet we invite the risk because to have never allowed such closeness would be its own death.

It is deeply rewarding when a client raises my awareness to aspects of life not given proper credence. Unbeknownst to him, Tom reminded me to withhold cold words, let warm ones flow, and savor moments; even those as bittersweet as when he held the bony hand of his withered Annie. Aside from increasing my awareness of the moment, Tom offers the possibility of life after loss. Anyone who embarks on a therapeutic relationship suggests the possibility of hope. Tom is trying, and I suppose that is the least any of us can do.

I may fear the future at times, but I needn’t allow its uncertainty to hinder my present. Instead, I embrace the moment; feel my wife’s breath on my cheek, or her heartbeat in my ear. If I accrue enough of those sacred moments, I will one day reflect on my openness to love, my reluctance to invite regret, and my newfound hope all wounds can heal.