Lately, no conversation with my father ends without at least one solid gripe about his brother’s conservative political beliefs. They have been divided for some time now; my uncle, a minion of Donald Trump; my father, an apostle of Bill Maher. So entrenched are they in their respective positions, they utilize an emotional distance to ease the tension. In the absence of direct conflict resolution, my father turns to me because it’s easier for him to grouse to a third-party than to accept differences and enjoy their common bonds.

After the conversation ends, anxiety kicks in, and I worry about how holding grudges erodes his health, and creates isolation I know he fears. Because they are septuagenarian, my focus turns toward minutes melting away until one of them dies, and the other is doomed to wonder how late life ideology supplanted brotherhood in order of importance.

To cope with our anxiety about death, higher functioning parts of our brain suppress perseveration about death in order to allow us to function. If we focused on death constantly, we would be paralyzed by anxiety. However, some awareness of mortality motivates us to maximize quality of life, and nothing promotes quality of life more than relationships. If we fool ourselves into believing there is an abundance of time to spare, we might waste some of it waiting for apologies rather than letting our own guard down, and making the first move.

The political rift between my father and his brother mirrors a religious differences between me and my younger brother. Whereas I am a person of faith, my brother is a staunch atheist who gags at the mention of God. Although I could allow our differences to divide us, I would be devastated if I lost his presence in my life, and we accept each other for who we are. I often diffuse tension with humor by insisting his hatred belies an undying love for God. Because I want that for my father, I jump into fixer mode to repair the relationship, even though my father never asked for a repair man, and I often end up overpowered by his obstinacy

Sadly, my dad’s grudge is not the only one by which I have been emotionally impacted.

A family with whom I am close recently imploded, and as of now seems irreparable. As is often the case, money is involved, and resentment related to who gets the spoils, and who feels cheated resulted in a fight in which depending on perspective, each was aggressor and victim. Sadly, it took one moment of emotional explosion to reduce the lifelong accomplishments of a deceased parent to a catalyst of division.

Of the three siblings, two no longer speak, and the third is dragged into the disagreement because the other two refuse to relent. That sibling is now forced to expend energy assuring the others she is impartial. When a grudge occurs between siblings in one generation, the ripple effect that spans multiple generations. Because two siblings refuse to resolve conflict, cousins see each other less, and they have no idea why. At large family gatherings, aunts and uncles of advanced age wonder aloud why one of the siblings has stopped showing up at parties.

I wonder what would happen if we were privy to our death date.

Crunch time is a strong motivator, and we often wait until the last-minute to study, do taxes, or renew licenses. Even though it is uncomfortable to work under such pressure, cramming seems to work for some people. One of the reasons I keep my grudges to a minimum is because if I learn I will die tomorrow, I won’t want to spend my waning moments cramming in apology and reconciliation. Unfortunately, far too many people wait until the end to make their peace, leaving no time to enjoy relationships. This is not the only way other generations play a role in grudges.

I’ve worked with many parents exhausted by their children’s tantrums, but who lack insight into their own, and often believe children operate in a vacuum. For some reason, parents don’t realize children’s behaviors are a product of familial influence, and they are shocked when I shine a light on them in therapy. When children peer into the adult grudge world, they learn everyone is right, no one is wrong, and “sorry” is a sign of weakness. Those lessons become imprinted, and when conflict arises later in life, child brain overpowers adult brain, and those same lessons are refered to as a defense mechanism.

When contemplating ingredients of grudge in my life, fear of vulnerability is a chief culprit. I have avoided saying “I’m sorry” or “I was wrong” because I believed those responses showed a weak hand, and exposed me to further threat. Every living creature is biologically hardwired to protect itself from injury, but humans experience the added complexity of fearing emotional wounds. Therefore, keeping people away through grudges ensures we won’t incur further injury. But it is an unfortunate byproduct of our avoidance of emotional wounds that we risk never repairing relationships, feeling the healing power of forgiveness, and experiencing intimacy.

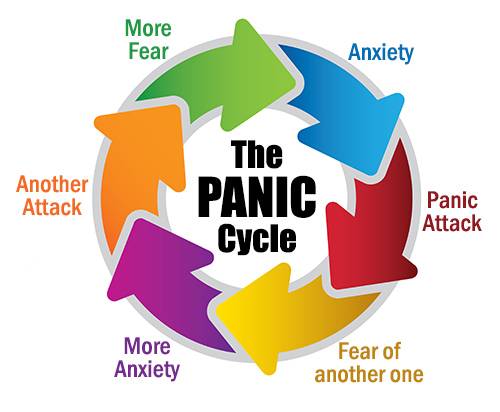

Grudges are also exhausting to maintain because they require constant fortification of walls built with negative thoughts. Those thoughts create mental strain that wears on us after prolonged periods. Furthermore, a person willing to hold one grudge is likely to hold many, and if we cut ourselves off from enough people, subsequent isolation results in anxiety from lack of connectivity.

It benefits us to examine the role grudge plays in our lives, the effect it has on our loved ones, and the energy it exhausts. Ultimately, if we sustain dysfunctional dynamics, the next generation inherits the pattern. Heightened awareness of our patterns provides enough insight to initiate change, and while current dynamics are rooted in generational patterns, it only takes one generation to rip up those roots, establish new ones, and plant patterns that will never need to be broken.

One Comment

Anonymous

Wow Vin….your words are powerfully thought provoking….yes, confronting resolutions before death is easier than dealing with we shoulda woulda coulda…but now it’s too late…why didn’t we??